John Green, the author of The Fault in Our Stars, released his latest novel in five years, titled Turtles All the Way Down in October. Let’s say that it is one of the best books I have read in a long time.

Considering that the last books I had read were titles like The Scarlet Letter and The Crucible, it doesn’t set the bar very high. Turtles All the Way Down had me devouring every word and staying up to unreasonably late hours because the book was just too good to wait to read more.

The book follows sixteen-year-old Aza Holmes, a girl diagnosed with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). In this story, her and her friend try to solve the mystery of a fugitive billionaire Russell Pickett, whom she conveniently knows the son of. The story is not only a thrilling adventure, but it becomes deeply personal when it delves into the mind of Holmes.

Turtles All the Way Down discusses and describes mental illness like no other book has. Green has managed to make the manic scribbles of thoughts into sharp, eloquent phrases that resonate with a lot of his readers. Like Holmes, Green has suffered through OCD, making the novel that much more real.

Now, time for some spoilers. Please pick up this article once you have finished the book, if you haven’t already. You have been warned.

This book talks about death. A lot. You would think that his book about cancer kids would talk about death more. But, you are mistaken. You see, the characters in Turtles All the Way Down are not only teens struggling with their own baggage, but they are also philosophers. Aza philosophizes about death and the ripples it makes in people’s lives. She has lost her father and Davis, Russell Pickett’s son, has lost his mother. They both think a lot about whether or not Davis’s father is dead and what the effects of it would be on him and his little brother, Noah.

As mentioned above, mental illness is one of the main themes of Turtles All the Way Down, especially OCD. People tend to associate OCD with repetitive behavior that is easy to describe and visualize, which is true in Aza’s case with the wound on her thumb she constantly picks at and disinfects, but it also about having intrusive thoughts, something more difficult to talk about. Green does this beautifully, giving the OCD a voice in her mind and at some points, it seems like Aza is talking to her OCD. Green doesn’t romanticize this illness; he paints it as a civil war.

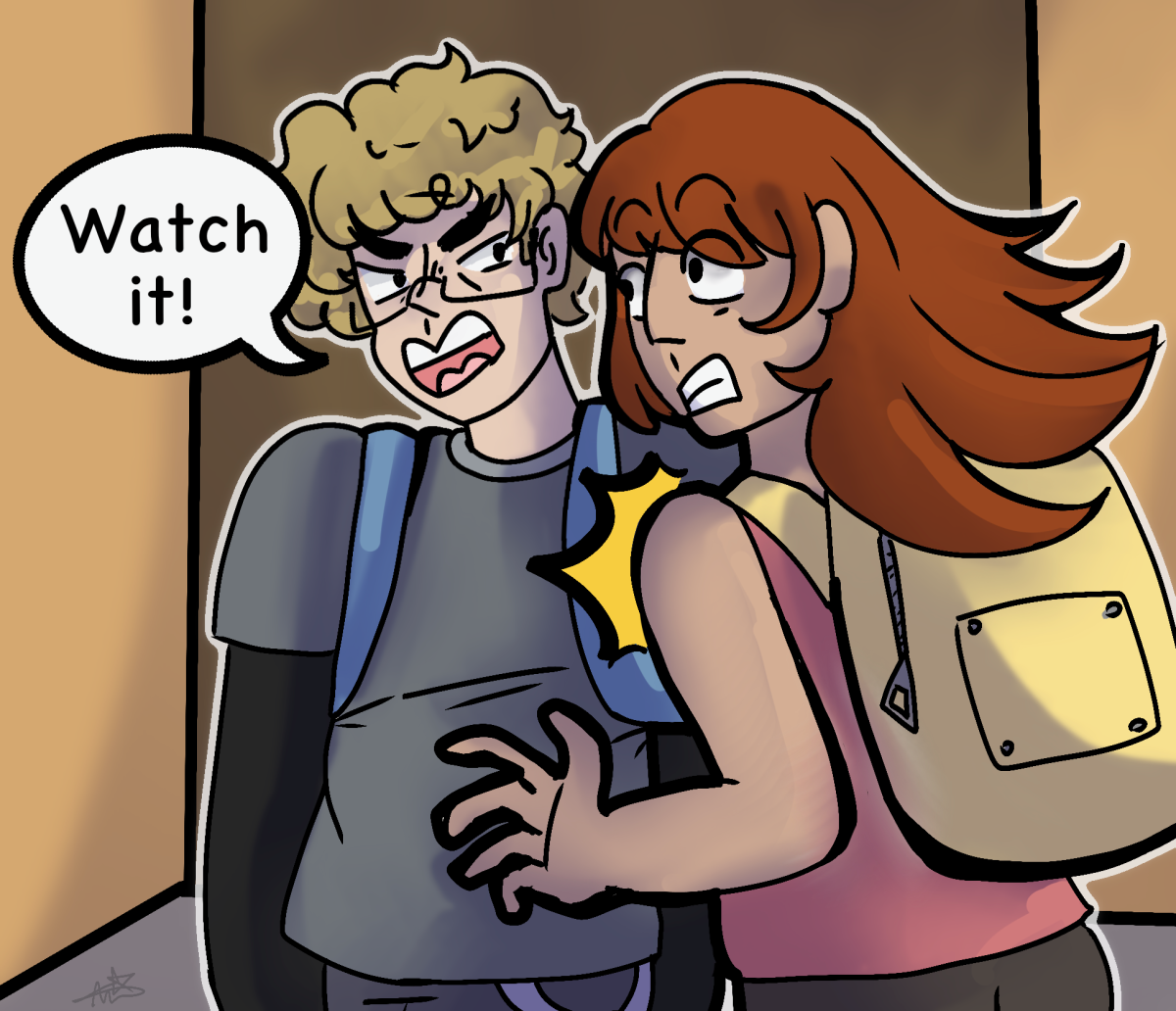

The love plot of the novel doesn’t take over the other parts, as it sometimes does in Green’s other novels. In fact, Aza and Davis don’t seem to have a connection. Aza longs to be with him, but her OCD tells her that this isn’t possible, listing thousands of different reasons (all of them germophobic) why she can’t be with him.

The end doesn’t complete this story with a pretty little bow. It does not tie up the story happily, because this isn’t a fairy tale. This is a tale about reality and the things people are actually facing. To sympathise and understand Aza is to be human. You don’t need to be diagnosed with OCD to understand the suffering she is going through.

Overall, this story was one of Green’s best works. It was real and raw, not sparing or sacrificing any details about Aza’s mental illness. Turtles All the Way Down was Green’s much awaited fifth book and it certainly lived up to the hype. If you want a relatable, moving book that will give you a much-needed cry at the end, check out Turtles All the Way Down at your local bookstore or elsewhere.